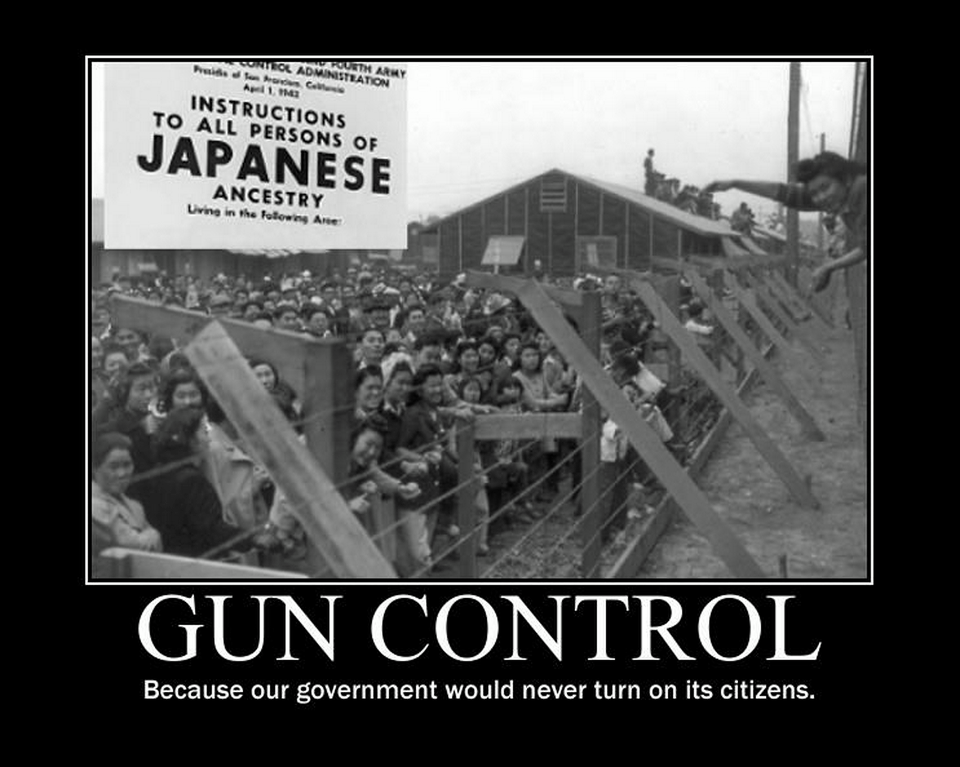

Stories add rich and personal details that generate an emotional connection to what was and what can be.”Īmerica is a nation of immigrants. They frame events, add context to the past beyond a history of facts. David Mas Masumoto’s words complement the purpose of the TOR project: In honor of the many contributions of the Japanese-American community and in recognition of the need to stop history from repeating itself, We are proud to direct our district’s Time of Remembrance Oral Histories Project (TOR). We work in a school district that was once home to a hard-working community of Japanese-American farmers, who transformed the region into beautiful, productive strawberry fields. Following the signing of Executive Order 9066, the history of the Elk Grove-Florin region was abruptly and forever changed. Thanks to a beautiful article in Friday’s SacBee from California farmer, journalist, and author David Mas Masumoto, we are reminded of the importance of standing up and speaking out on behalf of targeted groups. Virtually overnight, an entire group of people lost their jobs, their homes, and their constitutional rights. Nearly 40 years later, the federal government formally acknowledged that “race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership” motivated this mass incarceration-not “military necessity.” During the Reagan-Bush years Congress moved toward the passage of The Civil Liberties Act in 1988 which acknowledged the injustice of the internment, apologized for it, and provided $20,000 to each incarceration camp survivor as a means of reparations.Seventy-five years ago today, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, authorizing the removal of over 120,000 people of Japanese descent, many of them citizens, from the West Coast.

The internment of persons of Japanese ancestry during World War II sparked great constitutional and political debate. The Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco reported these citizens had suffered $400 million dollars in losses. When World War II drew to a close, the camps were slowly evacuated and no person of Japanese ancestry living in the United States was ever convicted of any serious act of espionage or sabotage. Persons who were deemed ‘disloyal’ were sent to a segregation camp at Tule Lake, California. However, eating in common facilities and having limited work opportunities interrupted other social and cultural routines. As four or five families with their sparse possessions squeezed into and shared tar-papered barracks, life consisted of some familiar patterns of socializing and school. Prohibited from taking more than they could carry into the camps, many internees lost their property and assests as it was sold, confiscated or destoryed in government storage. DeWitt signed the 108 Civilian Exclusion Orders and directives that would enact Roosevelt’s order across the West Coast.īy the fall of 1942, all Japanese Americans had been evicted from California and relegated to one of the ten concentration camps built to imprison them. At the Western Defense Command headquarters in the Presidio of San Francisco, Commander Lieutenant General John L. The order authorized the War Department to designate military zones where persons of ‘enemy’ ancestry would be excluded.

Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 out of “military necessity”. Courtesy of Library of Congress, Farm Security Administration & Office of War Information Collection, LC-USZ62-34565įebruary 19, 1942, ten weeks after the attack on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Photo by Dorothea Lange, San Francisco April 1942.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)